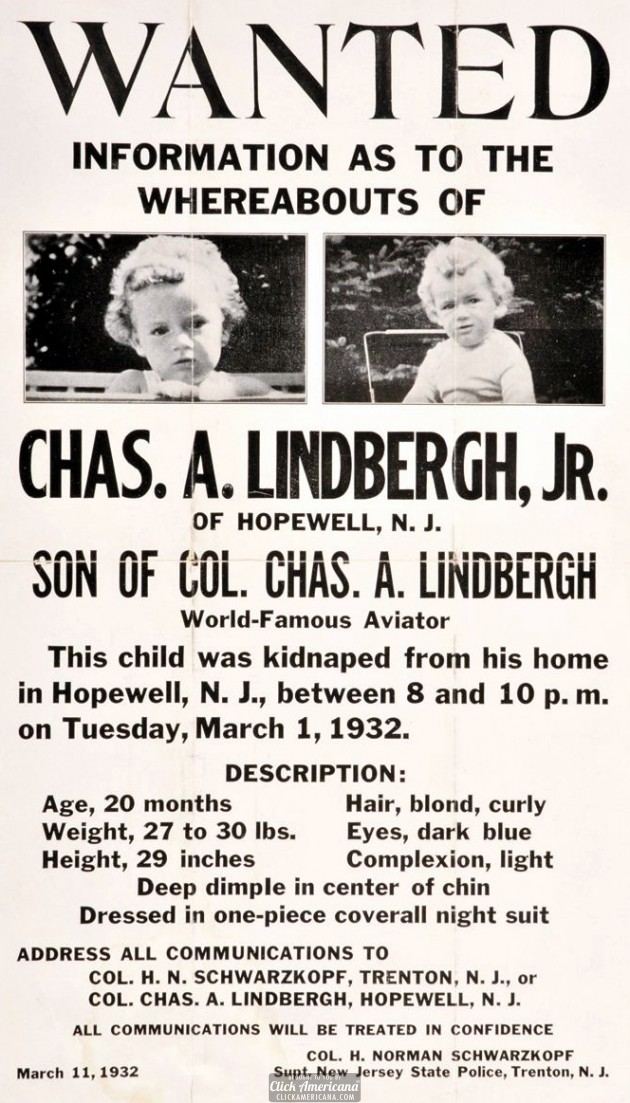

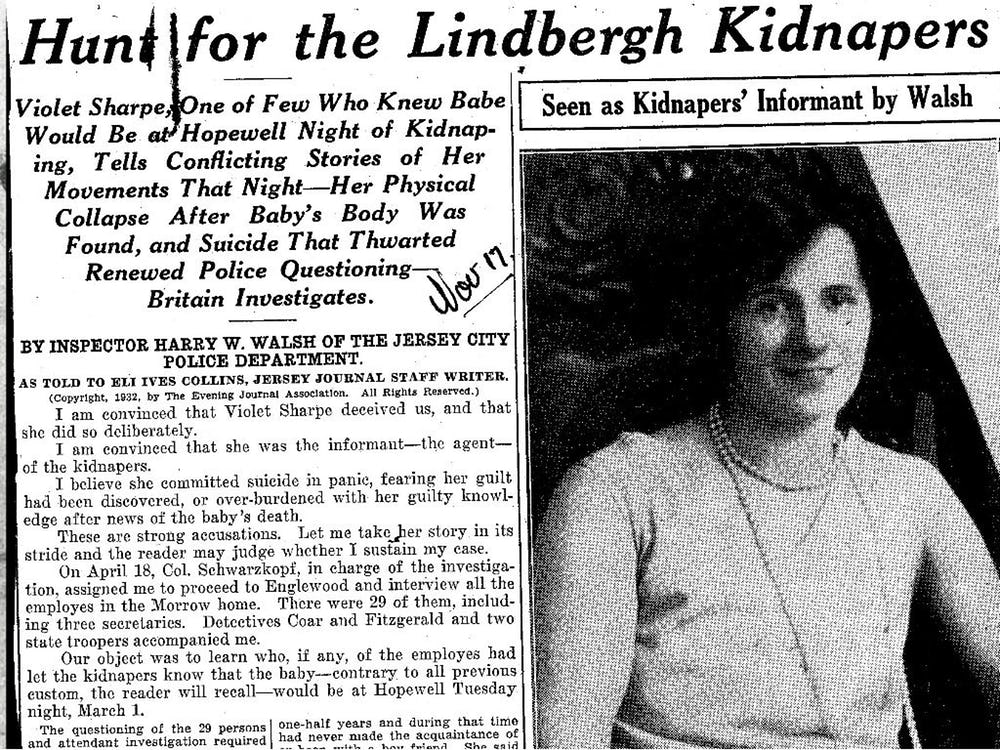

See Night Train to Perdition, Act I, for a summary of Murder on the Orient Express, and Night Train to Perdition, Act II, for a summary of related true-crime cases, including the kidnap and murder of Charles Lindbergh, Jr. The post you are reading details the forensic science responsible for the capture and conviction of one of the kidnappers, in particular the wood evidence provided by the ladder used in the kidnapping.

The Wooden Witness

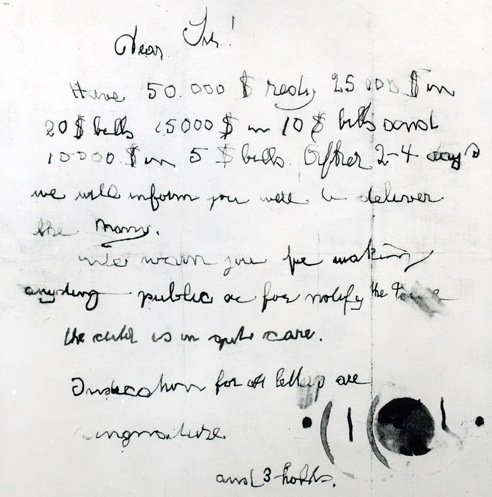

As noted in Act II, two key pieces of evidence were discovered immediately following the crime at the Lindbergh estate: a handwritten ransom note and a custom ladder. In their preliminary examination of the three-sectional ladder, the investigators postulated that the user was neither too tall nor too short and was left handed. The left handedness of the user was based on the pattern of saw blade cuts in the wood as well as the placement of the ladder to the right of the nursery window, which would allow the user to navigate entry into the nursery from his left side. The runners used in the ladders appeared to resemble wood crates that were used to protect bathtubs during transit, and police reported that the ladder was similar to those used with pipe organs.

Silver nitrate interacts with salt deposits found in human sweat and shed with fingerprints, which can then be visualized with ultraviolet light.

In the middle of 1932 and still at a loss for any leads, the investigators turned to the federal government for assistance. They sent the ladder, a chisel that was also found at the Lindbergh estate, and a soil sample to the Department of Justice. Drawing on the expertise within various federal departments, the DOJ sent samples from the ladder to the US Forest Service, of which 7 samples were sent to the Forest Products Laboratory in Madison, WI, a joint research venture with the Forest Service. Upon receipt, FPL Director Carlisle P. Winslow told Arthur Koehler, considered the nation’s top wood identification expert, to disregard all other projects and immediately identify the source of the wood in the Lindbergh kidnapping ladder. To do so, Koehler would apply his specialty in xylotomy, which is the art of preparing sections of wood for microscopic examination.

The Wood Expert

Arthur Koehler had established himself as a skilled xylotomist and had been serving as an expert witness in criminal trials following his promotion to the Head of Wood Technology at the FPL. He had recently testified in the murder trial of John Magnuson regarding the source of wood used by the criminal to encase a bomb, which led to a conviction. Koehler had even offered his assistance to Lindbergh after the kidnapping with a personal letter:

I read further in the newspaper about that homemade ladder left behind by the fellow who had done the crime and I grew excited. You see, that ladder, because it was made of wood, seemed just like a daring challenge.

Within a few days after that I wrote a letter to the Lindbergh baby’s father, saying I thought it might be possible to trace that ladder’s members until the wood matched up with other wood so as to compromise the man involved. Of course, I’m no Sherlock Holmes, but I have specialized in the study of wood. Just as a doctor who devotes himself to stomachs or tonsils or human vertebrae narrows down his interests to a sharp focus on the single field of his pet passion, so I, a forester, have done with wood.

He did not receive a response from Lindbergh.

Less than one week after receiving samples from the kidnapping ladder, Koehler had identified the various sources as Douglas fir, paper birch, Ponderosa pine, and Southern pine through comparisons with the FPL’s library of wood specimens. After submitting his report to the Department of Justice, Koehler wanted to continue helping with the investigation, his goal to make the ladder a “wooden witness.”

The Wooden Autopsy

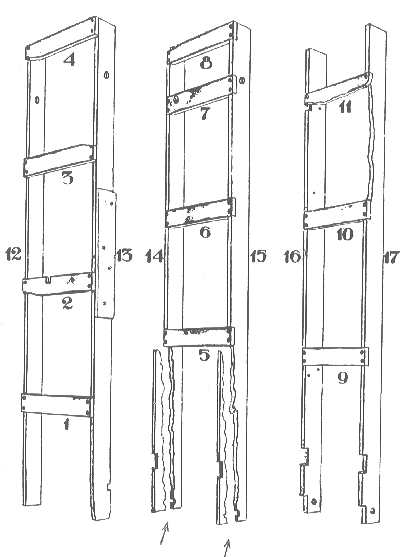

In early 1933, the New Jersey State Police would take Koehler up on his offer. Koehler was given full access to the ladder, which he dismantled to perform an “autopsy.” Each rung and rail was numbered, measured, and calipered. Koehler identified the source for each piece and closely examined the components for marks made during the assembly of the ladder. As relatively few sources of wood were used to construct the ladder, Koehler concluded “that the maker had a limited amount of material to choose from.”

Among all the pieces of the kidnapping ladder, Rail 16 seemed to offer the greatest potential for confirmatory evidence to match to a criminal. Rail 16 was North Carolina pine (the same as Rails 12 and 13), but it was more knotty and had not been machine planed. Rather, it had been hand-planed on both edges, leading Koehler to believe that the rail was worked down from a wider piece of wood:

Why he planed both edges of rail 16 is a mystery unless it was rough edged to begin with. The edges were not always at right angles to the face, and scratches made by the plane wobbled back and forth along the edge…the scratches left by a hand plane on both edges of this rail were exactly the same as those on one side of each of the [cleats], proving conclusively that they were made by the same plane, and presumably at approximately the same time, probably when the ladder was made.

Furthermore, Rail 16 had four nail holes that had been made by square-cut or 8-penny iron nails, which had been phased out of production by the end of the 1800s in favor of cheaper wire nails made from soft steel. In the 1930s, square-cut nails were still used in home construction, and the regular spacing of the nail holes in Rail 16 suggested they may have come from a building.

Keen to pursue multiple avenues of investigation, Koehler also fully characterized the marks from the machine planer used on Rails 12 and 13. He sent letters to the known manufacturers of wood planers to inquire as to which mills they may have sold the characteristic planers, and then solicited the mills for samples for examination. From April to September 1933, Koehler sent a total of 1596 requests and received 23 samples. Despite the small number of samples, he was able to identify Rails 12 and 13 as having been planed in a mill in South Carolina by examining the planer knife marks microscopically and measuring the marks to 1/100th of an inch. Ultimately, Koehler was unable to trace the kidnapper(s) based on Rails 12 and 13 because the Bronx lumber yard from which it was likely sold was a cash-only business.

Meanwhile...

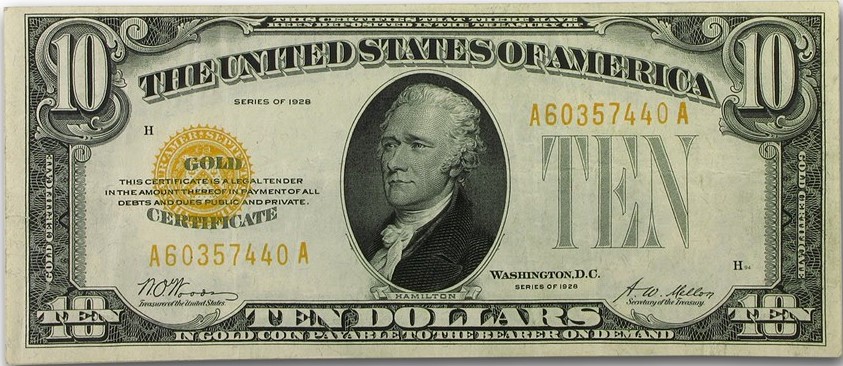

At the same time that Koehler was examining the wood of the kidnapping ladder, the police were actively tracing the ransom money. The $50,000 that was paid on behalf of the Lindbergh family by the go-between John Condon primarily comprised $20 and $10 gold certificates. Elmer Irey, an IRS accountant, proposed this mechanism to allow for easier tracing of the ransom money as the gold certificates were being phased out of circulation. The remaining ransom money was $5 bills with red seals and red serial numbers. All of the ransom money was printed in 1928, and a list of the serial numbers was sent to banks across the country.

Bills from the lot of ransom money would occasionally surface over the year and a half following its payment in 1932, most often in New York City. On 17 Sep 1933, a man paid for 98 cents of gasoline with a $10 gold certificate at a gas station in Manhattan. The station manager questioned the legitimacy of the bill and wrote down the man’s license plate number in its margin, in case the bank refused to deposit it. The manager questioned the customer about the bill, who was reported to reply, “I have a hundred more just like it.”

The license plate number was traced to Bruno Richard Hauptmann, an unemployed carpenter who was pulled over for a search shortly after leaving his house in the Bronx. When detectives found money in his wallet with serial numbers matching the ransom money, he was arrested.

The Wooden Key

Upon hearing of Hauptmann’s arrest, Koehler suggested that investigators take note of any lumber in his house that may have been used for Rail 16 as well as for any woodworking tools. In their first search of the house, investigators found a total of $13,750 of the ransom money and an automatic revolver concealed in wooden 2×4’s in the garage; they also found a large wooden plane with a nicked blade that could have been used in the construction of the ladder.

At the time of Hauptmann’s arrest, a news article reported that he once worked odd jobs at the National Lumber and Millworker Corp in the Bronx, where Koehler had traced Rails 12 and 13.

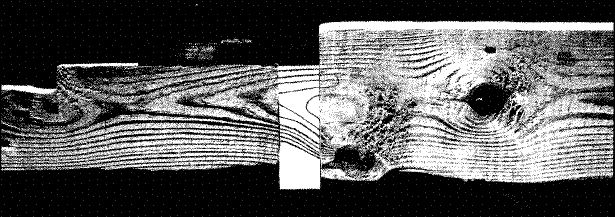

During a second search of Hauptmann’s attic, the investigators noted that the flooring comprised 27 pieces of 1×6 North Carolina pine. The final board on the south side was not the same length as the others, and they were able to discern that a piece approximately 8 feet long had been removed, leaving traces of saw marks and saw dust. A sample of the remaining board and the nails that had been used to connect the board to the joist were provided to Koehler for comparison.

Koehler observed nicks in the largest knife of the plane recovered from Hauptmann’s house that produced marks exactly matching those on Rail 16 and the pine rungs of the ladder. He concluded, “There is no question but [that] the rungs and rail were planed with that plane.”

The nails removed from the boards in Hauptmann’s attic fit into the holes in Rail 16 precisely, which lead Koehler to conclude “the board probably was removed from some of Hauptmann’s previous work either for others or for himself.” Koehler testified before the grand jury at the Hunterdon County Courthouse in Flemington, New Jersey, to these points. Along with testimony pertaining to the ransom note, ransom money, and various eyewitnesses, the grand jury found enough evidence to indict Hauptmann for the murder of Charles Lindbergh, Jr.

Meanwhile, Koehler continued his examination of Rail 16 in comparison to the wood removed from Hauptmann’s attic. He and the investigators took Rail 16 to Hauptmann’s attic, where it fit snugly into the place of the missing board. Koehler reflected that “Such a result could not happen as a mere coincidence.” Koehler had calculated the probability of all 4 nail holes matching the joists in Hauptmann’s attic perfectly as 1/1016, and he dismissed the possibility that this was mere circumstantial evidence.

1/1016, or 1 in 10 quadrillion, is the probability of 2 people randomly picking the same word out of 110 billion average-sized books.

Finally, he compared the grain, which is the appearance of the natural rings of a tree when it has been cut lengthwise to form a board:

It is a pattern that is always varied and yet the pattern of the grain in the ladder rail and floor board matched as perfectly as if the interrupted curving lines they plotted years ago had been etched within the tree just to be a trap for anyone who dared so to misuse wood as to form it into a kidnap ladder.

Every tree within itself has written all its history. The growth in spring shows white and pithy, but in the summer the slower growth becomes, in most trees, darker tissue. This is repeated year by year, and that is why these rings seem double and confuse those who try to say a tree is such and such an age. Count the band of white and black as one year’s growth. The board end of the piece of flooring that had been robbed to make a ladder showed its rings quite clear, and so did the ladder rail. A gap of one and three-eighth inches had been trimmed off, yet the rings matched.

The Wooden Evidence

At Hauptmann’s murder trial, Koehler testified his findings regarding Rail 16, but he was challenged by one of the defense lawyers, who stated, “We say that there is no such animal known among men as an expert on wood. That is not a science that has been recognized by the courts; that is not in a class with handwriting experts, with fingerprint experts or with ballistic experts. That has been reduced to a science and is known and recognized by the courts.” The judge allowed the defense council to cross-examine Koehler to ascertain the extent of his credentials. At the end of Koehler’s lengthy exposition regarding his publications in the field of wood science, the judge confirmed he was indeed a wood expert.

Koehler provided the court with complete details regarding his examination of the kidnap ladder, in particular Rail 16’s nail holes and grain. His xylotomical examination of the wood source and grain was essential to tying Hauptmann to the ladder used in the Lindbergh kidnapping. Following the testimony, Koehler was lauded as “the only real detective (in the case)” by the Reading, Pennsylvania Times, and The New York Post wrote,

The Hauptmann trial may go down in legal history less as the most sensational case of its time than as the case which brought legal recognition to the wood expert on par with handwriting, fingerprint and ballistic experts.

After 42 days of testimony from Koehler and others involved in the Lindbergh case, the jurors retired to deliberate on the verdict of Hauptmann. Less than 12 hours later, the jury returned with a verdict of guilty. The judge passed down a death sentence to the convicted murderer of Charles Lindbergh, Jr. Koehler’s testimony stood up to several appeals by Hauptmann, and on 03 Apr 1936, his death sentence was carried out by electric chair. Hauptmann never confessed to the crime and never indicated if other kidnappers were involved.

Koehler continued working as a wood identification expert but never in so sensational a trial as the Lindbergh case. He died in his home on 16 Jul 1967 at the age of 82. Although wood evidence continues to be valuable to forensic science, it has never again been at the forefront of a crime as in the Lindbergh kidnapping.