**Contains major plot spoilers for Murder on the Orient Express and a minor plot spoiler for The Double Clue.**

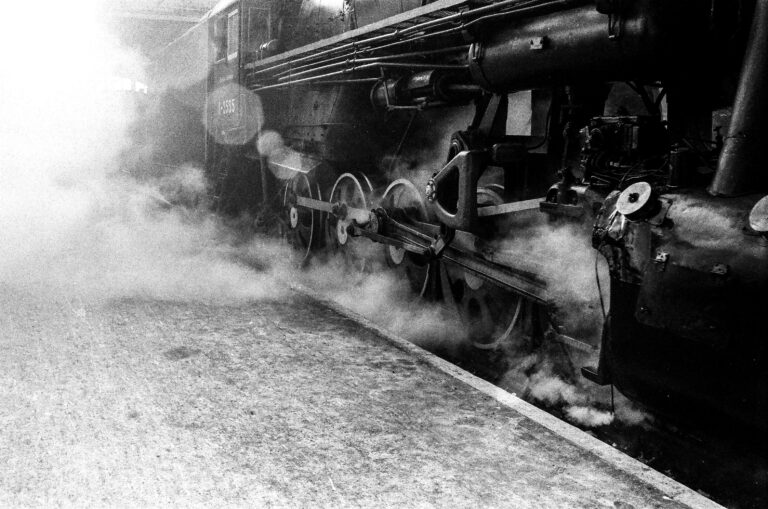

Murder on the Orient Express, written by Agatha Christie in 1933 and published the following year, is perhaps her seminal work. It is certainly the most famous, with 2 notable feature film adaptations and references in “SCTV” and “Parks and Recreation” (to name a few). It is easy to understand the longevity of the work: a locked room mystery set on a glamorous sleeper train wherein “a repulsive murderer has himself been repulsively, and, perhaps deservedly, murdered.” But while the mysteries at the center of the story are neatly wrapped up by Hercule Poirot as he enacts his own interpretation of justice, fascination around the true-crime case that influenced the book persists to this day.

Christie's Train Journeys

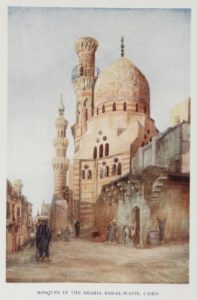

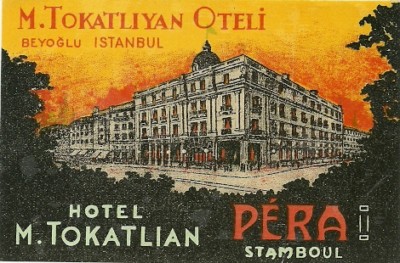

Christie first traveled on the Orient Express in 1928, shortly after the divorce to her first husband Archie was finalized. She had met a Commander and Mrs. Howe at a dinner party in London, and they urged the author to visit Baghdad via the Orient Express. During this trip, Christie stayed at the Tokatlian Hotel in Constantinople before continuing on to the Middle East. It was through friends she made at an archaeological dig near Baghdad that she would meet her second husband, Max Mallowan.

Christie’s time at archaeological sites with Mallowan inspired her novels Murder in Mesopotamia, Appointment with Death, and Death Comes as the End.

Mallowan was a 25-year-old archaeologist at the dig at Ur the following year when Christie returned. The pair traveled together back to England after Christie received a telegram that her daughter was ill, and they formed a close friendship. Letters turned into visits, and Mallowan proposed marriage to the 38-year-old Christie. They were married on September 11, 1930. Christie wrote Murder on the Orient Express during her time at an archaeological dig at Arpachiyah with Mallowan in 1933. The novel is dedicated to him, and he has been credited with originally suggesting the solution to the mystery to Christie.

But why aren’t they doing anything? Why, in the States, they’d have motored some automobiles along right away – why, they’d have brought aeroplanes…and

My daughter said I’d have no trouble at all – no trouble at all. I’ve never travelled to Europe before and I’ll never travel in it again.During this journey, she also encountered two Danish missionaries, a Hungarian Minister and his wife, and a Director of the Wagon Lits Company, all of whom inspired other characters in the story.

All Aboard ... for Murder

Murder on the Orient Express is Christie’s 16th book and her 8th mystery with Hercule Poirot as the central detective. The novel begins with Poirot returning from Syria, where he has participated in some unspecified intrigue. He arrives in Istanbul, checking into the Tokatlian Hotel (where Christie herself stayed). After receiving a telegram recalling him to London, Poirot books passage on the Simplon-Orient Express. Surprisingly, the train is fully booked, but Poirot conveniently enlists the help of his friend M. Bouc, a director of the Compagnie Internationale des Wagons-Lits, to secure a second-class compartment.

While at the Tokatlian Hotel, Poirot first notices a brash and despicable American traveler. Regarding the man, Poirot tells Bouc,

I could not rid myself of the impression that evil had passed me by very close.

While aboard the Orient Express, Poirot again encounters this individual, who calls himself Ratchett and attempts to enlist Poirot’s help with a series of threats he has received. Poirot refuses, telling him,

If you will forgive me for being personal—I do not like your face, M. Ratchett.

That night, Bouc offers his first-class compartment to Poirot, which is adjacent to Ratchett’s on the Calais Coach. Shortly before 1 o’clock, Poirot wakes to a cry from the American’s compartment, followed by an explanation in French that “it was nothing.” Poirot has also noticed that the train has been stopped for some time. An older American woman, Mrs. Hubbard, rings her bell and reports loudly that a man has been in her compartment, which is adjacent to Ratchett’s on the opposite side as Poirot’s. Poirot asks the conductor for some mineral water and learns that the train is stuck in a snowdrift. He manages to fall asleep but is awoken later in the night with a loud knock on his compartment door; when he looks down the corridor, he sees a woman in a scarlet kimono walking away from his door.

After this eventful night, the talk in the dining car centers around the interminable delay of the train journey, until it is discovered around 10 o’clock that Ratchett has been stabbed to death. The crime scene has several clues; in addition to the presence of the burned remains of flat matches and a piece of paper, a pipe cleaner, and a fine woman’s handkerchief embroidered with the letter “H”, the window to the compartment is open but there are no tracks in the snow, and the dead man’s watch has been stopped at 1:15. Ratchett had been stabbed 12 times across the chest and abdomen. A Greek doctor staying in the Athens-Paris Coach, Dr. Constantine, assists with the examination of the body and states,

The blows seem to have been delivered haphazard and at random. Some have glanced off, doing hardly any damage. It is as though somebody had shut their eyes and then in a frenzy struck blinding again and again.

Poirot Investigates!

Of course, Poirot is enlisted to solve this mystery and sets about interviewing all the passengers of the Calais Coach:

- Hector MacQueen: Ratchett’s young American secretary, who reports functioning more as a courier since the deceased knew no foreign languages; he describes the threatening notes received by Ratchett

- Pierre Michel: The Wagon Lit conductor, deeply shaken by the crime on his train

- Edward Henry Masterman: The English valet of the deceased, somewhat unaffected by the murder

- Caroline Martha Hubbard: An elderly American woman, who reports there was a man in her compartment around the time of the murder and also provides the button from a Wagon Lit conductor’s uniform that appeared in her compartment. She later recovers the murder weapon, a bloody dagger.

- Greta Ohlsson: A Swedish missionary, who was the last person to see Ratchett alive after mistakenly opening his compartment door

- Princess Natalia Dragomiroff: An aged Russian princess, with no notable clues to report

- Count Rudolph Andreyi: A Hungarian nobleman with little to report from the night of the murder

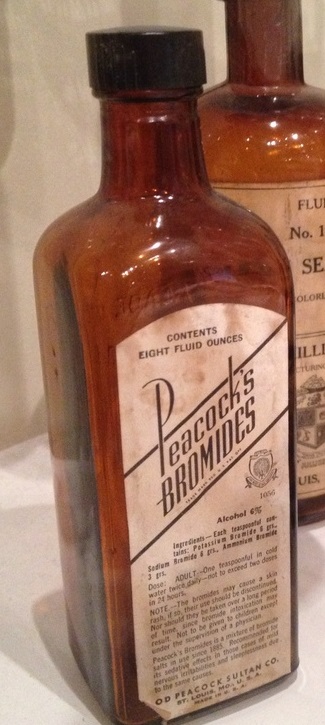

- Countess Elena Andrenyi (née Goldenberg): The wife to the Count, who took a sleeping draught the night of the murder

- Colonel John Arbuthnot: An English military officer, recently serving in India, who spoke with Hector MacQueen until nearly 2 o’clock the night of the murder

- Cyrus Hardman: Traveling as a typewriting ribbon salesman, he reveals he is a detective from McNeil’s Detective Agency in New York enlisted by Ratchett for his protection. According to Hardman, the deceased man said he feared a small dark man with a womanish voice.

- Antonio Foscarelli: An Italian automobile salesman based in the United States

- Mary Debenham: An English governess previously working in Baghdad, who reports seeing the woman in the scarlet kimono but denies that it was her

- Hildegarde Schmidt: The German maid to Princess Dragomiroff; she states she encountered a Wagon Lit conductor who was not Pierre Michel and was a small dark man with a womanish voice. She also seems to recognize the handkerchief found in the deceased man’s compartment.

Additionally, Poirot manages to ascertain the identity of the murdered man using the burned note fragment at the crime scene and some hat boxes. Ratchett was in truth the notorious American criminal, Cassetti, who was responsible for the kidnapping and murder of Daisy Armstrong. Daisy was the daughter of Colonel and Sonia Armstrong; she was abducted from the family’s home with a ransom demand for $200,000. After the ransom was paid, Daisy’s body was found, and it was evident that she had been dead for some time.

Mrs. Armstrong was pregnant at the time and gave premature birth to a still-born child; the mother died during childbirth. Colonel Armstrong, devastated at these compounded losses, died by suicide. Furthermore, Daisy’s French nursemaid, Susanne, was suspected of assisting in the crime and also died by suicide, though her innocence was subsequently proven. Cassetti was apprehended and charged with the crime, but due to his wealth and connections, he was acquitted on a technicality. He escaped from America. Christie drew obvious inspiration from the kidnapping and murder of Charles Lindbergh, Jr, which occurred the year before she wrote the novel.

Through his inquiries, Poirot manages to prove a connection between each of the passengers and the Armstrong case. In a stunning denouement, he reveals two potential solutions to the passengers when they are assembled in the dining car later in the day following the murder.

The first solution is that a stranger boarded the train after it departed Stamboul and used a Wagon Lits conductor uniform and pass key to enter Ratchett’s compartment–these items had been found in the luggage of Hildegard Schmidt during a search of the Calais coach. The stranger stabbed Ratchett and escaped into Mrs. Hubbard’s compartment, which is supported by Mrs. Hubbard sensing a man in her compartment and finding the missing button of the Wagon Lits conductor uniform. The stranger then escaped the train before it departed from the last station; the inconsistency in the time of the crime versus Ratchett’s watch may be explained by the deceased forgetting to adjust his watch when entering the Central European Time Zone.

One notable reveal by Poirot is that the “H” on the handkerchief is from the Cyrillic alphabet, corresponding to an “N” in the Latin alphabet, and therefore belongs to Natalia Dragomiroff. A similar device is used in Christie’s short story The Double Clue as well as in Season 11, Episode 11 of Murder, She Wrote (“An Egg to Die For”).

Several of the passengers (most vociferously M. Bouc and Dr. Constantine) note that this explanation fails to account for several small details of the crime. Poirot then recounts his second–and correct–solution. Every passenger in the Calais Coach on the night of the murder, save himself, had some connection to the Armstrong case. Conspiring together with Mrs. Hubbard–mother to Sonia Armstrong–as the ringleader, they decided to carry out a death sentence on the criminal during this journey on the Simplon-Orient Express. Twelve passengers (with the Count Andreyni standing in for his wife, Sonia Armstrong’s sister) stabbed Cassetti after Masterman had drugged his sleeping draft; like a firing squad, the death could not be ascribed to any one participant.

Faced with the two possible solutions, Poirot allows Bouc to decide which will ultimately be reported to the Yugoslavian authorities. The Director elects the former solution of a stranger boarding the train to commit the murder. Poirot accedes and “has the honour to retire from the case.”

Reception and Film Adaptations

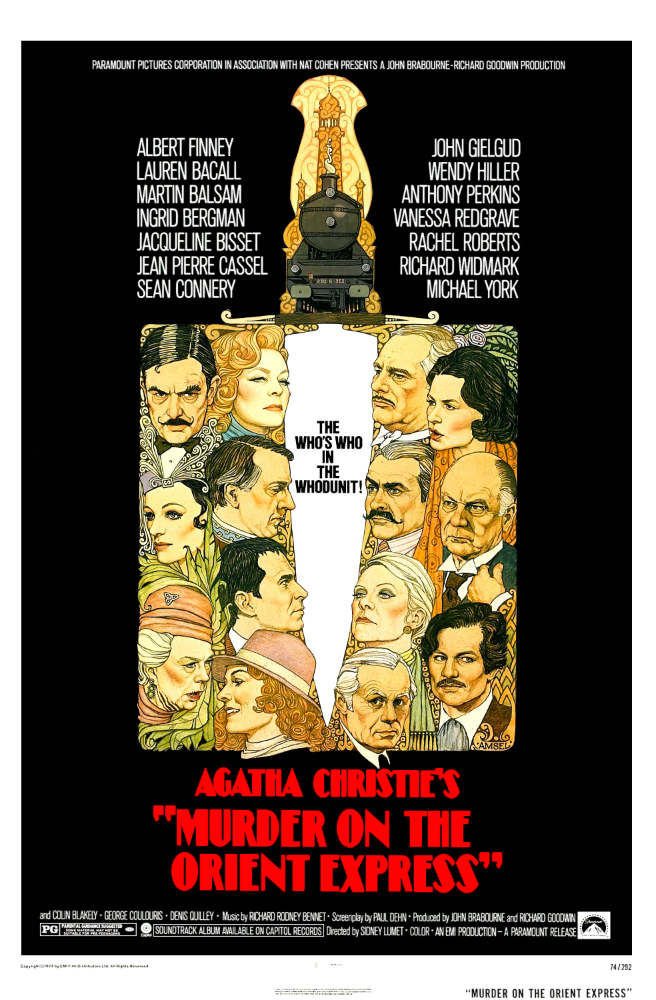

Murder on the Orient Express remains one of Christie’s most popular works and has been present in the zeitgeist since its publication. The novel has been adapted into 2 noteworthy feature films. While the 1974 version is fairly loyal to the source material, the 2017 version departs quite a bit and will not be further discussed.

Following the Miss Marple films released in the 1960s, Christie was hesitant to grant the film rights for any more of her work. It required some delicate finagling by Lord Louis Mountbatten, a naval hero and father-in-law to British film producer John Bradbourne. Eighteen months later, Christie granted the film rights to EMI. The resulting film, directed by Sidney Lumet, has an all-star cast and employed genuine Orient Express train cars on loan from the Compagnie Internationale des Wagon-lits Museum in France. At the age of eighty-four, Christie attended the movie premiere and appreciated the film. The adaptation became the highest grossing British film for a time.

While it is certainly an enjoyable–if improbable–story, part of the endurability of Murder on the Orient Express must be credited to the contemporary true-crime tale of the kidnapping and murder of Charles Lindbergh’s child. The original Crime of the Century parallels the tragic story of Daisy Armstrong and will be explored (in addition to some other related true-crime stories) in the next post.