**Contains major plot spoilers for The Mysterious Affair at Styles.**

See the previous post Dressed to the Strychnines, Act I for a summary of the creation of Agatha Christie’s first novel, The Mysterious Affair at Styles, as well as a synopsis of the book; see Dressed to the Strychnines, Act II for an in-depth description of strychnine poisoning in the context of Christie’s first novel. The post you are reading will describe the history behind the legal concept of double jeopardy in England and the United Kingdom.

Double Sin

In addition to the poisoning discussed previously, another clever feature of The Mysterious Affair at Styles planned by the criminals but ultimately foiled by Hercule Poirot was the use of double jeopardy to prevent one of the criminals (Alfred Inglethorp) from receiving justice. The plan, somewhat ill conceived, was for Alfred to be arrested for his wife’s murder and brought to trial, at which point he would produce a witness who would provide his alibi. This would result in his acquittal without the possibility of a second trial due to the legal principle of double jeopardy. This seems a very risky strategy, as was clearly shown by Poirot’s uncovering of multiple alibi witnesses before Alfred’s arrest. Had the police uncovered such witnesses, Alfred would never have been arrested and therefore not brought to trial.

In the United States, double jeopardy is prohibited by the 5th amendment to the constitution, which states “[N]or shall any person be subject for the same offence to be twice put in jeopardy of life or limb.” In England, double jeopardy was part of the common law for centuries and was formalized after the US constitution was ratified.

Origin in Antiquity

The notion that a person should not be punished twice for the same crime was proffered as early as Ancient Greece, with the Greek orator Demosthenes stating in 355 BCE that “the laws forbid the same man to be tried twice on the same issue, be it a civil action, a scrutiny, a contested claim, or anything else of the sort.” Even in antiquity, pleaders (precursors for barristers in the UK) sought loopholes to reopen cases upon which courts had already ruled. In Ancient Rome, The Digest of Justinian, which was a collection of writings of the contemporary Roman legal system in 533 AD, asserted that “[t]he governor must not allow a man to be charged with the same offenses of which he has already been acquitted” and that “a person cannot be charged on account of the same crime under several statutes.” In addition, double jeopardy was a component of Ancient Jewish law cited in the Talmud.

Pleaders have no direct corollary in the US legal system but can be thought of as legal scholars, counselors, or advocates.

Double Jeopardy in the UK

In English history, the first recorded instance of the use of double jeopardy was in 1201. Goscelin, the son of Walter, sought punishment via appeal against Adam de Rupe for killing Goscelin’s brother, Ailnoth. Adam’s defense consisted of stating that Alinoth’s wife had previously brought an appeal against him for the same crime, and during that trial, “he withdrew quit therin by judgment of the lord king’s court,” ie, he was acquitted. In Goscelin’s appeal, the court recognized this previous acquittal and also cited the fact that Goscelin was in Ireland at the time of the killing and could therefore bring no new evidence to the court.

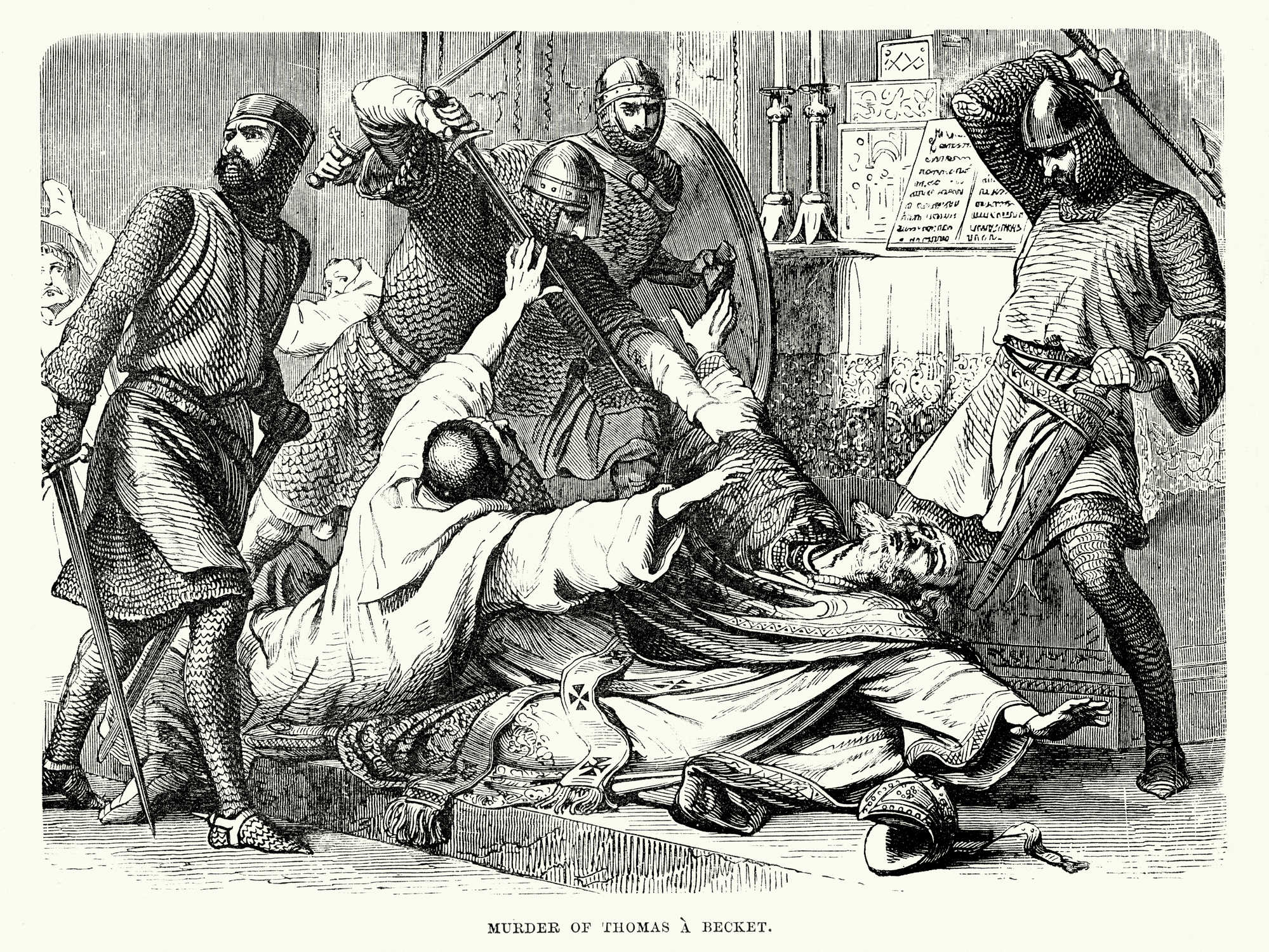

There are three theories as to how the notion of double jeopardy was introduced into British common law: that the principle was carried over from the continent, that it arose following the disagreement between Thomas Becket and King Henry I, or that it was merely a logical progression of the law.

A Normandy Import

The first theory suggests that double jeopardy immigrated to England following the Norman conquest in 1066. After William the Conqueror’s victory, the principle might have been introduced in England along with the other canon laws from the continent. This theory also posits that during the process of developing common law around this time, legal scholars applied concepts from Roman law that might have been discussed during their training in the church as most common law judges were members of the clergy.

The Murder at the Cathedral

The second theory is appropriately enmeshed in an important historical murder. After the Norman conquest, William the Conqueror appointed the Italian lawyer and theological scholar Lanfranc to be the Archbishop of Canterbury, who at the time was the head of the Catholic Church in England. At William’s encouragement, Lanfranc established a system of ecclesiastical churches that were regarded equally with the royal courts and prosecuted all criminal and civil cases in which a cleric was accused. This series of events can be viewed as recompense to the Pope by William for supporting his conquest of England.

T. S. Eliot’s play, Murder in the Cathedral, is about the assassination of Thomas Becket. The play includes verses inspired by The Musgrave Ritual, a Sherlock Holmes story:

Who shall have it?

He who will come.

What shall be the month?

The last from the first.

What shall we give for it?

Pretence of priestly power.

Why should we give it?

For the power and the glory.

Although Henry was victorious over the late Archbishop, the changes in the law were short lived. In 1176, the King reversed the constitutional provision that permitted a cleric to be further punished in the royal court, possibly due to Becket’s martyrdom and subsequent canonization as well as the persuasion from many of the royal judges, who were bishops and archdeacons. At this point, a strong precedent for double jeopardy would have been established.

Origination Unknown

The final theory on the origin of double jeopardy in English law suggest that it was a slow, natural progression without any influence from Roman law, which could have been enacted formally at any time. Its proponents offer as evidence that there were numerous exceptions to the rule during the first 500 years of English law. Furthermore, a case in 1203 (very soon after the showdown between Thomas Becket and King Henry I) is described as possibly violating the principle of double jeopardy. Following the trial of Reiner Reid for assaulting another man and cutting off his fingers, wherein Reid paid the victim 10 marks, the wronged man (surname Jordan) raised a civil appeal charging Reid with the same crime. Reid’s defense cited the double jeopardy principle, but given that all appeals were tried in the civil courts at the time and double jeopardy only applied to criminal offenses, it was a moot point.

During this time, the Court of King’s Bench also prohibited the practice frequently used by trial judges of excusing the jury when an acquittal was imminent to provide the prosecutor the opportunity to bring a stronger case in a new trial.

Back to Styles

At the time of Alfred Inglethorp’s trial—in the late 1910s had it transpired as the criminals intended—he would have been exonerated by an alibi witness and would have been protected by double jeopardy, as the murder of his wife was a capital offense. Provided that Poirot and the police did not uncover any substantial new evidence and appeal to the courts, Inglethorp would not have been able to be tried for his wife’s murder. In addition to the manipulation of chemistry, this scheme to exploit the English legal system is further evidence of the ingenuity of the criminals, which of course is no match for Poirot’s order and method.

Cards on the Table

After numerous campaigns by victims’ families and advocacy groups, the double jeopardy law in the United Kingdom was overturned in 2005 for serious crimes, such as murder, rape, and war crimes. In order to bring an acquitted defendant back to trial for the same crime, a sufficient amount of reliable and new evidence not available at the time of the original trial must be presented.

This change in the law arose in part due to the case of Stephen Lawrence, who was murdered in 1993 at the age of 18 by a group of racist men. During the first trial the subjects were acquitted, but Sir William MacPherson, a retired high court judge, released a report in 1999 that documented the institutional racism present in the Metropolitan Police during their investigation of the crime. The report also recommended that the guarantee of protection against double jeopardy be re-evaluated.

After the change in the law, the chief subjects were again brought to trial in 2011. Early the following year, they were found guilty. Several other investigations have been reopened in cases where acquittals were previously reached. Given the storied history of double jeopardy, this recent change would no doubt have inspired Agatha Christie to formulate another clever mystery plot.