**Contains major plot spoilers for The Mysterious Affair at Styles and a minor plot spoiler for A Caribbean Mystery.**

Formulating a Mystery

The previous post, What’s in a Dame?, provided a very brief biographical sketch of Agatha Christie up until her first novel, The Mysterious Affair at Styles, was accepted for publication in 1919. The novel was subsequently published in 1920.

Let us revisit Agatha at work in the Castle Chambers hospital dispensary a few years prior. In her autobiography, she states:

Unlike nursing, where there always was something to do, dispensing consisted of slack or busy periods. Sometimes I would be on duty alone in the afternoon with hardly anything to do but sit about. Having seen that the stock bottles were full and attended to, one was at liberty to do anything one pleased except leave the dispensary.

It was in this setting that Agatha plotted her first novel, which would logically employ poisoning. It was also obvious to her that her detective novel would include the detective’s friend “as a kind of butt or stooge,” as in the Sherlock Holmes stories. Regarding the plot, she describes considering the minutiae in a way that would forever be associated with her name and oeuvre:

The whole point of a good detective story was that it must be somebody obvious but at the same time, for some reason, you would then find that it was not obvious, that he could not possibly have done it. Though really, of course, he had done it.

She goes on to say:

At that point I got confused, and went away and made up a couple of bottles of extra hypochlorous lotion so that I should be fairly free of work the next day.

A 0.5% solution of hypochlorous acid in lotion was a common treatment for wound healing at the time.

Dramatis Personae

For the characters in Styles, Agatha observed her neighbors and fellow tram passengers for inspiration. Using the considerable imagination she had shown throughout her childhood, she created names and backstories based on the appearances of the people she encountered. In this way, she developed the characters of Emily Inglethorp, Alfred Inglethorp, and Evelyn Howard.

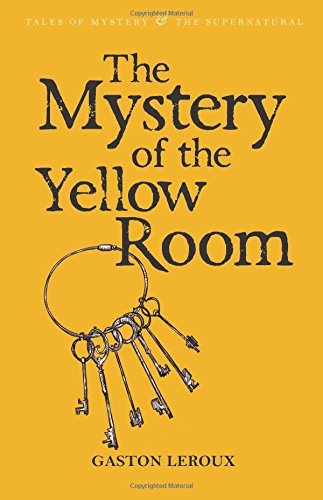

Creating her detective character was a more serious undertaking for Christie. She thought of Sherlock Holmes but considered herself unable to emulate him. She was not terribly keen on Poe’s Arsene Lupin, who was both a criminal and a detective. In her autobiography, she goes on to mention Rouletabille from Gaston Leroux’s The Mystery of the Yellow Room as a distinctive character similar to the one she sought to invent—“someone who hadn’t been used before.”

The Mystery of the Yellow Room was written by Gaston Leroux (author of The Phantom of the Opera) and published as a serial in 1907. The crime at the center of the novel is the assault of a young woman in a room within a French château that was locked from the inside—a locked room mystery. The protagonist of the novel, Joseph Rouletabille, is a journalist and amateur sleuth accompanied by his lawyer friend, who also narrates the novel. In addition to these tropes, Christie was no doubt inspired by Leroux’s inclusion of diagrams and floorplans describing the crime scene, a device which she would use throughout her novels.

The Genesis of Poirot

In addition to the influence from this recently published work of mystery fiction, Christie looked to her surroundings to create one of the most memorable detectives in the history of the genre, Hercule Poirot. In the nearby parish of Tor, a group of Belgian refugees from the Great War had settled comfortably. Christie considered it plausible that one of these refugees could be a retired police detective, attempting to live a solitary life tending to a garden but being continually interrupted to solve perplexing crimes. In her autobiography, Christie notes she settled on the phrase “little grey cells” during this development of Poirot and that he would be a very tidy man. The first name of her detective naturally derived from the mythological character of Hercules, but Christie could not recall from where conceived of “Poirot”; she thought perhaps she had seen it in a newspaper.

For the next few weeks, Agatha pieced together the puzzle mystery in her head. She completed the first draft of the story in longhand, and then typed the manuscript on her sister’s old typewriter. Despite this progress, Agatha struggled to put the complete story together, and particularly in the central portion of the book. At her mother’s suggestion, she took a one-week vacation in Dartmoor. During long walks on the moor, Agatha spoke through the various scenes she proposed for the book—to herself—before writing them out. After this vacation, she was more satisfied with the near-complete book.

The surname of Poirot is thought to originate from the French word for “pear” (poire) and roughly translates as “a grower of pears.” As described in The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, following Poirot’s retirement from his service as private detective, he becomes an ardent grower of vegetable marrows (a type of squash) rather than pears.

A Mysterious Affair

The Mysterious Affair at Styles was refused by the first two publishers to whom Agatha sent it: Hodder & Stoughton and Methuen’s. She sent it to a third publisher, whose name she cannot recall in her autobiography, which also declined to publish it. The final publishing group that Agatha tried—The Bodley Head—held onto the manuscript for nearly two years before informing Christie that they were considering publishing the novel with a few changes. Primarily, Agatha was asked to change the last chapter, which originally occurred during a court scene where Poirot essentially testified the solution to the mystery. Her method to accede to this request by her publisher would become a Christie mainstay throughout her novels and short stories.

After accepting this feedback, Christie eagerly signed her contract from The Bodley Head, which committed her to 5 additional novels; in her zeal she neglected to read this clause. Thus began this celebrated history of 66 novels and 14 collections of short stories with The Mysterious Affair at Styles. After the first five novels and a collection of short stories, Agatha fulfilled her contract with The Bodley Head, and most of her work was published by William Collins & Sons.

Happy Families

The novel begins in the small Essex country town of Styles St. Mary with Arthur Hastings, an officer in the British Army, who is recuperating from an injury suffered during World War I. By coincidence, Hastings stumbles upon an old school friend, John Cavendish, who invites Hastings to stay at his family’s country manor, Styles Court, for an interminable period of time. During tea one afternoon, Hastings is asked his future plans and at this point, the reader is offered the first hint of Hercule Poirot as Hastings speaks of his own desire to become a detective:

I came across a man in Belgium once, a very famous detective, and he quite inflamed me. He was a marvelous little fellow. He used to say that all good detective work was a mere matter of method. My system is based on his—though of course I have progressed rather further. He was a funny little man, a great dandy, but wonderfully clever.

The inhabitants of Styles Court are somewhat ill at ease because the family matriarch, Emily Inglethorp, who is the stepmother of John and his brother Lawrence, has remarried a much younger man, Alfred Inglethorp. Particularly outraged at the pairing is Mrs. Cavendish’s companion, Evelyn Howard, though it is revealed early in the novel that Inglethorp is her distant cousin. Rounding out the household members are Mary Cavendish, John’s wife; Cynthia Murdoch, Mrs. Inglethorp’s ward; and Dorcas, the loyal maid.

Several weeks after Hastings first arrives at Styles, the house is disturbed very early one morning by Mrs. Inglethorp in her agonizing death throes. As the household gathers in a vain attempt to help the poor woman, she cries out the name of her husband (noticeably absent from the scene) and dies. Also missing from the scene is the ward Cynthia, who was unable to be roused by Mary.

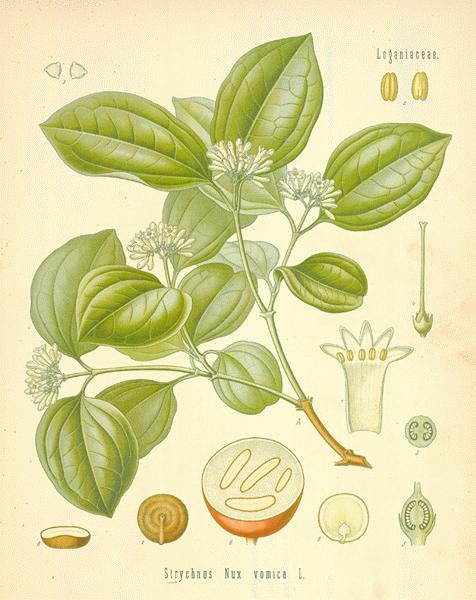

Given Mrs. Inglethorp’s strong convulsions prior to death, strychnine is immediately suspected. The police and family quickly consider Alfred the prime suspect, as he would benefit financially by his wife’s death. As luck would have it prior to Mrs. Inglethorp’s death, Hastings happened to encounter the detective friend of whom he spoke at tea, who is staying with a collective of Belgian refugees in the village. Thus, we are introduced to Hercule Poirot.

Poirot was an extraordinary looking little man. He was hardly more than five feet, four inches, but carried himself with great dignity. His head was exactly the shape of an egg, and he always perched it a little on one side. His moustache was very stiff and military. The neatness of his attire was almost incredible. I believe a speck of dust would have caused him more pain than a bullet wound. Yet this quaint dandyfied little man who, I was sorry to see, now limped badly, had been in his time one of the most celebrated members of the Belgian police. As a detective, his flair had been extraordinary, and he had achieved triumphs by unraveling some of the most baffling cases of the day.

Poirot begins his own investigation, examining the crime scene and interrogating witnesses throughout the village. Both he and the police uncover that Alfred Inglethorp (or someone who closely resembled him) had purchased strychnine in the village. He is able to dissuade the police from arresting Alfred Inglethorp because he establishes the prime suspect’s alibi with no fewer than five corroborating witnesses.

Dramatic Denouement

Suspicion quickly falls onto the next most likely suspect, John Cavendish, who would inherit Styles Court after his stepmother’s death. The prosecution asserts that John killed his stepmother before she had the opportunity of disinheriting him following an argument that they had earlier that day. Before a verdict is reached, Poirot unravels the case in a flurry of activity and requests that all interested parties (along with Inspectors Japp and Summerhaye from Scotland Yard) meet with him. During that meeting, Poirot reveals:

- Mary Cavendish had administered nonlethal doses of a narcotic to Cynthia and Mrs. Inglethorp the night of the latter’s death in order to gain access to her room for a letter containing evidence of John Cavendish’s extramarital affair, which did not exist.

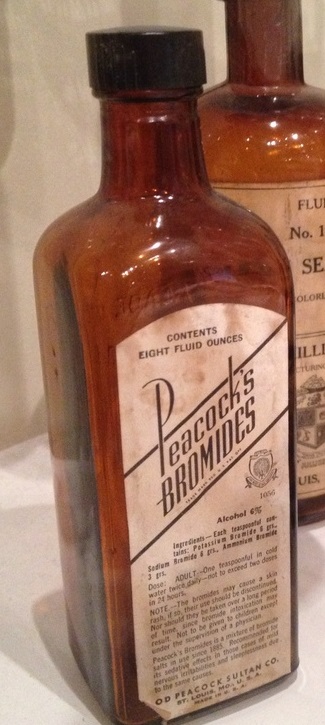

- Mrs. Inglethorp was fatally poisoned as a result of the combination of the potassium bromide that she habitually took in combination with her strychnine tonic. The narcotic delayed the action of the strychnine until the early morning hours.

- The perpetrators were Alfred Inglethorp and Evelyn Howard, who were lovers. Mrs. Inglethorp became aware of the affair in the afternoon before her death when she discovered an incriminating letter in her husband’s writing desk. Evelyn had poured one of the bromide powders into the strychnine tonic several days prior, and the resulting precipitate would be fatal; the two criminals merely had to wait until Mrs. Inglethorp took the final, concentrated dose.

The characters of Cynthia (a hospital dispenser) and Lawrence (an aspiring writer) describe Agatha Christie in combination, so it is appropriate that they are engaged by the end of the novel.

There are several other side plots in the novel, which are wrapped up neatly as well. Lawrence and Cynthia become engaged, and John and Mary rekindle their love, leading Hastings to think:

Who on earth but Poirot would have thought of a trial for murder as a restorer of conjugal happiness!

In addition to introducing the frequently used ending scene with the final explanation of the crime occurring in a room in which all interested parties were gather, The Mysterious Affair at Styles also marked the first instance of one character looking over another’s shoulder and seeing something surprising, puzzling, or frightening, when Lawrence glances nervously over Hastings’s shoulder at Cynthia’s door lock during Mrs. Inglethorp’s death scene. Christie would use this device throughout her work, perhaps most notably in A Caribbean Mystery. Another element in Styles destined for reuse was a secret pair of lovers colluding together to commit a crime while overtly quarreling to dispel suspicion.

However, there are two components of this mystery that will be the focus of two upcoming posts: strychnine poisoning and double jeopardy.